It is no longer the extraordinariness of the image, but rather its familiarity that lends credibility to the representation of how these immigrant women have made new lives in the city.

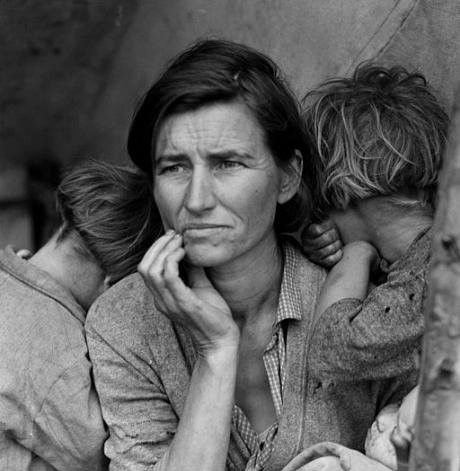

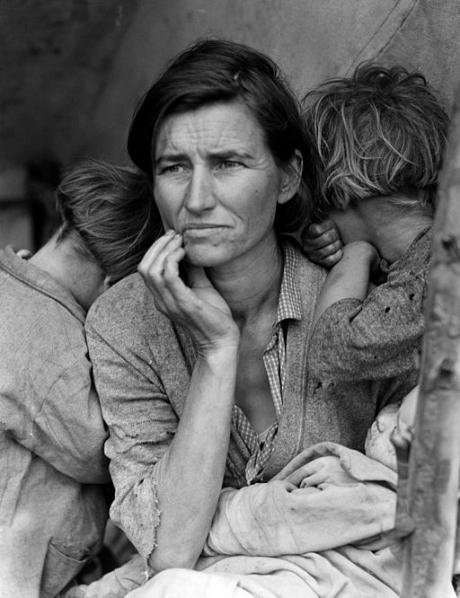

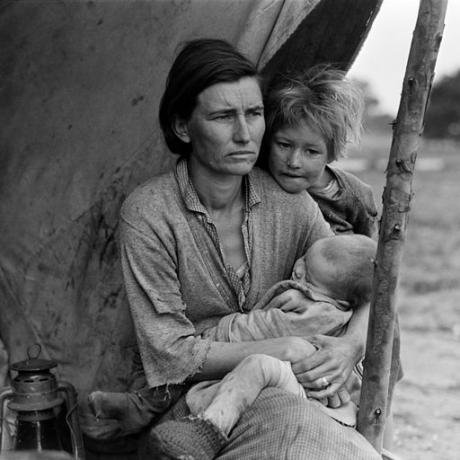

"Migrant Mother", California, 1936. Wikicommons/ Dorothea Lange. In a world where the selfie has become ubiquitous and where images constantly drift past our line of vision, it seems reasonable to wonder if photographs matter. Thanks to the advent of the smartphone, we can all be photographers. This technological dexterity serves to remove whatever trace of the magical there remained in photography against the grain of modernity’s emphasis on rationality. There was a time when a photograph was an event. When the sitter surrendered to timelessness for an instant and when the photographer, in a representative act that sought to capture experience, demonstrated the alchemy of time and place. All that has long since changed.

Photography in the digital era exemplifies modernity’s narcissism and unstable fluidity. In entering the muddy waters of the ordinary and the everyday, it risks anonymity, even irrelevance. This may fundamentally alter the place of photography in our world, but it does not in any way lessen it. Against the grain of a surfeit of the visual and in the face of a surplus that threatens to obscure it, the photograph has shifted to assuming a vernacular that speaks of, and to, the world around us. In so doing, we constitute ourselves via the image as much as through experience. With the ambiguity and ambivalence that has always been part of this medium, images both make up the everyday as much as human subjects do and, simultaneously, announce the uniqueness of the everyday. Yes, most images sorely lack punctum – that ability to pierce the viewer and leave an imprint that Barthes wrote about – but to imagine the world devoid of images is also to imagine the world halved through the loss of its reflection in the mirror. It is to imagine the world halved again by the closing in of horizons of memory and possibility, and halved yet again by the loss of the face of the other. It is to imagine a world unable to progress due to the breakdown of a vital medium that helps us make sense of reality, or even just glimpse it perhaps, through representation.

When photography was first invented in the nineteenth century, it was hailed as a revolution in man’s relationship with time and place. The power to intervene in the passage of time, to rupture the latter in the closing of a shutter, saw photography become a vital tool for intervening in the world. Its documentary power made the camera a companion of travellers, early anthropologists and explorers. Documentary photography became a medium through which inequalities or injustices were exposed, a witness to suffering that drew the viewer in. In bringing into focus those who might otherwise have been relegated to obscurity, photography mediated inequalities and opened a space where otherness could be framed and engaged with. The result was often pedagogical, if not charitable, as in the case of Dorothea Lange’s iconic image of the Migrant Mother, a photograph that did more to raise funds for those affected by the Depression than many newspaper reports on the same topic.

Images today still retain something of that aura that made the topic, if not the subject, memorable. More to the point, the visual has become a key instrument in mediating the world around us. It is as vital as language itself, and equally potent in symbolic significance. Furthermore, in the same way as the self now engages with the selfie and evolves through and around it, so do images provide us with a means to navigate social contexts and engage with them. We, as photographers, are also our own subjects. We have become the other who occupies the space of the frame – the other whom we cannot distinguish ourselves from, but whose image spurs us on to negotiate the complexities of time and place.

The Women of the World: Home and Work in Barcelona project is conceived within this context where alterity features in the everyday, and in the here and now. Few figures can match that of the migrant in signaling the presence of the other in our midst. The Women of the World project sought to trace the paths of subjects who are otherized in numerous ways, on account of immigration, gender and ethnicity. The oral narratives of their trajectories that were collected would have been incomplete without the visual, that other vernacular that empowers the scattered subjects of globalization to give meaning to their world.

A fundamental method that the project rested on was to ensure that the subjects determined how and where they were photographed. Their approval was also sought in the final selection of images, turning these into collaborative acts that echoed the narrative act of engaging in interviews. In this sense, it is no longer the extraordinariness of the image, but rather its familiarity, indeed its necessity, that lends credibility to the representation of how these immigrant women have remade home, found work and made new lives in the city. The visual and the oral act as two media that complement one another, in an effort to map the voice onto the face, and so also give a face to the voice, of the subject.

"Migrant Mother" alternative version. Wikicommons/ Dorothea Lange. Some rights reserved.If photography matters today, it is not because it heralds big revolutions or because it marks the extraordinary. On the contrary, it is because it marks the ordinary, the everyday, the transient subjects of modernity, seen most emblematically in the context of migration. The French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, a master of the everyday, once said that ‘it is an illusion that photos are made with the camera… They are made with the eye, heart and head.’ He might have added that it is not the photographer alone who makes the image, but the viewer too. To see and to listen is to know and to feel. It is to engage in the adventures of alterity and to enter into the imaginative realms of the familiar unfamiliar. This, then, must be why photography matters.