Yet again, a photograph erupts into the collective sightline: a picture of a father and child who drowned whilst attempting to cross over from Mexico to the United States.

The media ensures that shock ricochets through the public by disseminating evidence of the deadly realities of undocumented migration as if it were something new. Julia Le Duc’s image, taken on the banks of the Río Grande, of a father and child who drowned whilst attempting to cross over from Mexico to the United States, has circulated widely in recent days as yet another reminder of the barbarity that hounds the undocumented. Some say the image is too painful to look at. It is, after all, at once a scene all too familiar and all too alien. Protective to the end, the father has bound his child to him with his T-shirt. In death, the child’s arm remains trustingly around his neck, as it must have so many times in life when he carried her. Face-down, though, they turn rapidly from individuals into icons, of the sort that conjure up a range of responses, from sorrow, to solidarity, to sordid sentimentality.

Le Duc’s image has been compared to that of Aylan Kurdi, as America’s version of the horrors lived in the Mediterranean in the wake of conflict in Syria. The photograph fits, in fact, into a longer line of imagery of migrant despair, such as Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, set in the Californian dust bowl at the time of the Depression. If destitution is a tragedy, then it gains eloquence when coloured with the despair of parents who cannot provide for their children. At least, the subjects of Lange’s image were alive. Not so in the case of little Valeria and her father from El Salvador. Like Aylan Krudi, like the unknown migrant in Javier Bauluz’s award-winning image of 2002, the subjects of Le Duc’s photograph join the numbers of those who die at borders.

There is little doubt that the media’s dissemination of, and responses to, Le Duc’s photograph have centred around a sense of shock. There has been great interest in this family’s story, in their identities, dreams and desires. Despite the fact that it is a very well documented fact that many current border policies, especially those of the US, set the scene for the unnecessary deaths of migrants in transit, the media’s response has been one of apparent public unpreparedness and unawareness that such horrors do happen. No doubt, the image arrests. However, there is the risk that responses that stop at shock act as allies to the very political contexts that led to the deaths of the subjects, because they form the political bedrock for the establishment of states of exception and are fundamental to processes of securitization, violence and control.

Shock, experienced as a mix of horror and sensationalism, is what the media has trained the public to seek evermore via images in lieu of real engagement with world affairs. Shock turns the image into spectacle, otherizing the subjects through precisely that sense of recognizably human suffering that is, however, well removed from ‘us’ as viewers. Shock draws out gut responses, often in passing, not rational, well-thought strategies for change. Shock causes us to reel, to react, as if powered by adrenaline, and then the feeling passes, until the next image presents itself to raise the response once more. The shock factor is an ally of consumer culture, commonly deployed by the advertising and entertainment industries, for marketing reasons, ultimately leading to stupefaction in the viewer.

Little has been achieved to secure the lives of migrants.

To value Le Duc’s photograph for all that it implies, the viewer needs to move beyond that initial shock and ask questions – and, in doing so, must embrace what is not seen and what cannot be encapsulated in one image: the politics of the US, Mexico and Central America; the realities of migration in the region considered against the vast economic and political divisions that prevail; regional policies that alienate the human and elevate sovereignty; the glaring global failure to govern international migration in humane and dignified ways.

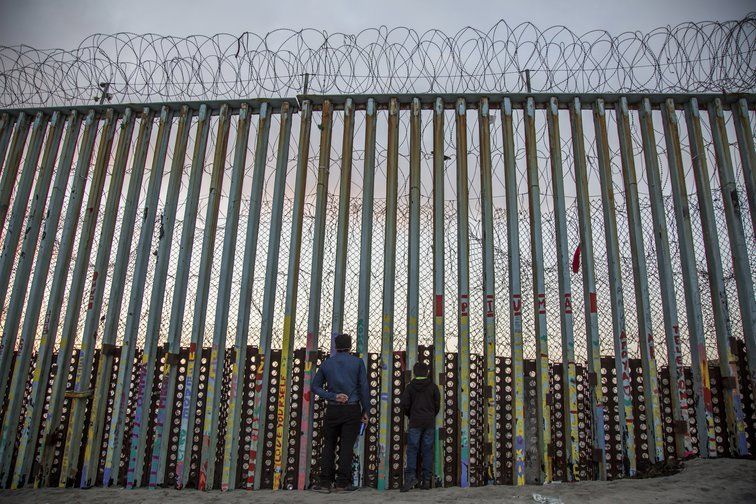

One may begin by asking what it was that provoked this father to take his little daughter with him whilst attempting to cross over into the United States. Why did he do so, when presumably he could have tried to cross on his own and left her with her mother? The many news items that have zeroed in on this image fail to address this question. Perhaps, though, the answer lies in the fact that many migrants attempting to cross international borders, especially those deadly ones that demarcate the global south from the global north, will take children with them. The chances of humane treatment, if caught, of possible assistance, and of leniency with regard to stay are always greater when minors are involved – even, perhaps, in the United States under the Trump Administration. The truth is that the barbed wire of international border policies both obstructs the undocumented and shape the choices they make within their limited margins.

What is objectionable beyond the senseless deaths of this child and her young father is the chasm that separates their bodies on the river bank from the safe and privileged spaces of global, regional and national policy makers as they deliberate at an infuriatingly slow pace on ways to ‘manage’ migration without upsetting the very status quo that led to their deaths and to the deaths of countless, indeed quite literally innumerable, other migrants in transit. The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration was adopted in December 2018, albeit in a process that revealed the great fractures between states that confirm the contentiousness of the very topic of migration. Little has been achieved since then to secure the lives of migrants. Without coordinated international governance, especially between those wealthy and states and regions that most uphold their borders and their poorer neighbours, the chances of implementing the compact are minimal. The US border with Mexico, a state that co-led the negotiation of this global compact, has turned instead into a crucible for the toxicity with which migration is regarded. Caught between the influx of its poorer neighbours to the south and the heavily securitized border policies of the US to the north, Mexico plays an ambivalent role as recipient of migrants and as guardian of the gateway to the American nightmare that awaited Valeria and her father. For as long as concerns over sovereignty, power, regional control and borders prevail over human worth, the waters of the Río Grande will continue to wash, most likely, over the bodies of many others.

What purpose, then does the photography of migrant realities serve? How can viewers respond in useful ways, to ensure that policies change? The media’s overwhelming focus on the personal story casts a veil over the political and the public, making it hard to engage proactively, especially because those crucial links between the seen and the unseen, the personal and the political, the public and the individual are deliberately obstructed and the media relies on ‘our’ forgetting, on our lust for more news, more shocks and more stories. The aim is, ultimately, to perpetuate and fortify the control of any burgeoning polity of the people.

Photography plays an interesting role in engaging solidarity. Photographs that are powerful are three-dimensional and open-ended. They take the viewer out of what is known into what an encounter with what is strange, close but also distant, troubling because it is uncharted. Photographs can not only shock: they can unsettle. They can stage protest. They can demand dignity. Photography can build bridges, taking viewers via the image into an imagination of those spaces inhabited by ‘others,’ both the living and the dead. To engage with an image proactively, as opposed to passively, is not to be shocked and stop there – it is to take a risk. Julia Le Duc’s brilliant, memorable, heart-wrenching image offers just such an opportunity. It builds precisely this bridge to risk and it is up to each viewer, each of us, to determine how to take that journey up: through how we vote, how we treat our neighbours, how we regard ‘others,’ be they minorities of any kind, how we respond to populism, how we object (or not) to failures of policy, how we respond to policies that we know can lead to fatal consequences.